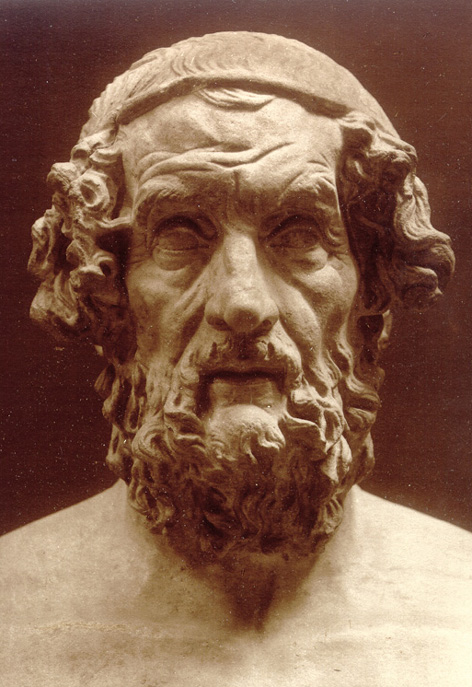

Homer

(X Century B.C.)

Homer is a poet of the subtle physical.

SRI AUROBINDO

Opening of the Iliad

Sing to me, Muse, of the wrath of Achilles Pelidean,

Murderous, bringing a million woes on the men of Achaea;

Many the mighty souls whom it drove down headlong to Hades,

Souls of heroes and made of their bodies booty for vultures,

Dogs and all birds; so the will of Zeus was wholly accomplished

Even from the moment when they two parted in strife and in ager,

Peleus’ glorious son and the monarch of men Agamemnon.

Leto’s son from the seed of Zeus; he wroth with their monarch

Roused in the ranks an evil pest and the peoples perished.

For he insulted Chryses, priest and master of prayer,

Atreus’ son, when he came to the swift ships of the Achaeans

Hoping release for his daughter, bringing a limitless ransom

While in his hands were the chaplets of great far-hurtling Apollo

Twined on a sceptre of gold and entreated all the Achaeans.

“Atreus’ son and all you highgreaved armèd Achaeans;

You may the gods grant, they who dwell in your lofty Olympus,

Priam’s city to sack and safely to reach your firesides.

Only my child beloved may you loose to me taking this ransom,

Holding in awe great Zeus’ son far-hurtling Apollo.”

Then all there rumoured approval, the other Achaeans,

Deeming the priest to revere and take that glorious ransom,

But Agamemnon it pleased not; the heart of him angered,

Evilly rather he sent him and hard was his word upon him.

“Let me not find thee again, old man, by our ships of the Ocean

Either lingering now or afterwards ever returning,

Lest the sceptre avail thee not, no nor the great God’s chaplets.

Her will I not release; before that age shall o’ertake her

There n our dwelling in Argos far from the land of her fathers

Going about let loom, ascending my couch at nightfall.

Hence, with thee, rouse me not, safer shalt thou return then homeward.”

So he spoke and the old man feared him and heeded his bidding.

Voiceless along the shore by the myriad cry of the waters

Slowly he went; but deeply he prayed as he paced to the distance,

Prayed to the Lord Apollo, child of Leto the golden.

[Sri Aurobindo’s translation — 1901 ca]

Sri Aurobindo’s remarks:

«A fancy was started in Germany that the Iliad of Homer is really a pastiche or clever rifacimento of old ballads put together in the time of Pisistratus. This truly barbarous imagination with its rude ignorance of the psychological bases of all great poetry has now fallen into some discredit; it has been replaced by a more plausible attempt to discover a nucleus in the poem, an Achilleid, out of which the larger Iliad has grown. Very possibly the whole discussion will finally end in the restoration of a single Homer with a single poem, subjected indeed to some inevitable interpolation and corruption, but mainly the work of one mind, a theory still held by more than one considerable scholar.»

«Poetry at a certain stage or of a certain kind expresses this turn of the human mentality in word and in form of beauty. It can reach great heights in this kind of mental mould, can see the physical forms of the gods, lift to a certain greatness by its vision and disclose a divine quality in even the most obvious, material and outward being and action of man; and in this type we have Homer.»

«Homer gives us the life of man always at a high intensity of impulse and action and without subjecting it to any other change he casts it in lines of beauty and in divine proportions; he dealt with it as Phidias dealt with the human form when he wished to create a god in marble. When we read the Iliad and the Odyssey, we are not really upon this earth, but on the earth lifted into some plane of a greater dynamism of life, and so long as we remain there we have a greater vision in a more lustrous air and we feel ourselves raised to a semi-divine stature.»

«It is the adventures and trials and strength and courage of the soul of man in Odysseus which makes the greatness of the Odyssey and not merely the vivid incident and picturesque surrounding circumstance, and it is the clash of great and strong spirits with the gods leaning down to participate in their struggle which makes the greatness of the Iliad and not merely the action and stir of battle.»

«The Odyssey is a battle of human will and character supported by divine power against evil men and wrathful gods and adverse circumstance and the deaf opposition of the elements, whose scenes move with an easy inevitability between the lands of romance and the romance of actual human life, losing nowhere in the wealth of incident and description either the harmonising aesthetic colour or the simple central idea.»

«In many things Homer seems to make a point of repeating himself. He has stock descriptions, epithets always reiterated, lines even which are constantly repeated again and again when the same incidents returns in his narrative: e.g. the line,

Doupêsen de pesôm arabêse de teuche’ ep’ autô.

“Down with a thud he fell and his armour clangoured upon him.”

He does not hesitate also to repeat the bulk of a line with a variation at the end, e.g.

Bê de kat’ oulumpoîo karênôn chôömenos kêr.

And again the

Bê de kat’ oulumpoîo karênôn âUixâsa.

“Down from the peaks of Olympus he came, wrath, vexing his heart-strings” and again, “Down from the peaks of Olympus she came impetuously darting.” He begins another line elsewhere with the same word and a similar action and with the same nature of a human movement physical and psychological in a scene of Nature, here a man’s silent sorrow listening to the roar of the ocean:

Bê d’akeôn para thîna poluphlois boio thalassês —

“Silent he walked by the shore of the many-rumoured ocean.”

[…] This is natural when the repetition is intended, serves a purpose; but it can hold even when the repetition is not deliberate but comes in naturally in the stream of the inspiration. I see, therefore, no objection to the recurrence of the same or similar image such as sea and ocean, sky and heaven in one long passage provided each is the right thing and rightly worded in its place. The same rule applies to words, epithets ideas. It is only if the repetition is clumsy or awkward, too burdensomely insistent, at once unneeded and inexpressive or amounts to a disagreeable and meaningless echo that it must be rejected.»

«Bê de kat’ oulumpoîo karênôn chôömenos kêr.

Homer’s passage translated into English would be perfectly ordinary. He gets the best part of his effect from his rhythm. Translated it would run merely like this: “And he descended from the peaks of Olympus, wroth at heart, bearing on his shoulders arrows and doubt pent-in quiver, and there arose the clang of his silver bow as he moved, and he came made like unto the night.” His words are too quite simple but the vowellation and the rhythm make the clang of the silver bow go smashing through the world into universes beyond while the last words give a most august and formidable impression of godhead.»

«Why has there never been a real rendering of Homer in English? It is not the whole truth to say that no modern can put himself back imaginatively into the half-savage Homeric period; a mind with a sufficient fund of primitive sympathies and sufficient power of imaginative self-control to subdue for a time the modern in him may conceivably be found. But the main, the insuperable obstacle is that no one has ever found or been able to create an English metre with the same spiritual and emotional equivalent as Homer’s marvellous hexameters.»

Opening of the Odyssey

Sing to me, Muse, of the man many-counselled who far through the world’s ways

Wandering was tossed after Troya he sacked, the divine stronghold,

Many cities of men he beheld, learned the minds of their dwellers,

Many the woes in his soul he suffered driven on the waters,

Fending from fate his life and the homeward course of his comrades.

Them even so he saved not for all his desire and his striving;

Who by their own infatuate madness piteously perished,

Fools in their hearts! for they slew the herds the deity pastured,

Helios high-climbing; but he from them reft their return and the daylight.

Sing to us also of these things, goddess, daughter of heaven.

Now all the rest who had fled from death and sudden destruction

Safe dwelt at home, from the war escaped and the swallowing ocean:

He alone far was kept from his fatherland, far from his consort,

Long by the nymph divine, the sea-born goddess, Calypso,

Stayed in her hollow caves; for she yearned to keep him her husband.

Yet when the year came at last in the rolling gyre of the seasons

When in the web of their wills the gods spun out his returning

Homeward to Itacha, — there too he found not release from his labour,

In his own land with his loved ones, — all the immortals had pity

Save Poseidon alone; but he with implacable anger

Moved against godlike Odysseus before his return to his country.

Now was he gone to the land of the Aethiopes, nations far-distant, —

They who to either hand divided, remotest of mortals,

Dwell where the high-climbing Helios sets and where he arises;

There of bulls and of rams the slaughtered hecatomb tasting

He by the banquet seated rejoiced; but the other immortals

Sat in the halls of Zeus Olympian; the throng of them seated,

First led the word the father divine of men and immortals;

For in his heart had the memory risen of noble Aegisthus

Whom in his halls Orestes, the famed Agamemnonid, slaughtered;

Him in his heart recalling he spoke mid the assembled immortals:

“Out on it! how are the gods ever vainly accused by earth’s creatures!

Still they say that from us they have miseries; they rather always By their own folly and madness draw on them woes we have willed not.

Even as now Aegisthus, violating Fate, from Atrides

Took his wedded wife and slew her husband returning,

Knowing the violent end; for we warned him before, we sent him

Hermes charged with our message, the far-scanning slayer of Argus,

Neither the hero to smite nor wed the wife of Atrides,

Since from Orestes a vengeance shall be, the Atreid offspring,

When to his youth he shall come and desire the soil of his country.

Yet not for all his words would the infatuate heart of Aegisthus

Heed that friendly voice; now all in a mass has been paid for.”

Answered then to Zeus the goddess grey-eyed Athene.

“Father of ours, thou son of Cronus, highest of the regnant,

He indeed and utterly fell by a fitting destruction:

So too perish all who dare like deeds among mortals.

But for a far better man my heart burns, clear-eyed Odysseus

Who, ill-fated, far from his loved ones suffers and sorrows

Hemmed in the islands girt by the waves, in the navel of ocean,

Where in her dwelling mid woods and caves a goddess inhabits,

Daughter of Atlas whose baleful heart knows all the abysses

Fathomless, vast of the sea and the pillars high on his shoulders

In his huge strength he upbears that part the earth and the heavens;

Atlas’ daughter keeps in that island the unhappy Odysseus.

Always soft are her words and crafty and thus she beguiles him.

So perhaps he shall cease from thought of his land; but Odysseus

Yearns to see even the distant smoke of his country upleaping.

Death he desires. And even in thee, O Olympian, my father,

Never thy heart turns one moment to pity, nor dist thou remember

How by the ships of the Argives he wrought the sacrifice pleasing

Oft in wide-wayed Troya. What wrath gainst the wronged keeps thy bosom?

[Sri Aurobindo’s translations — 1913 ca]