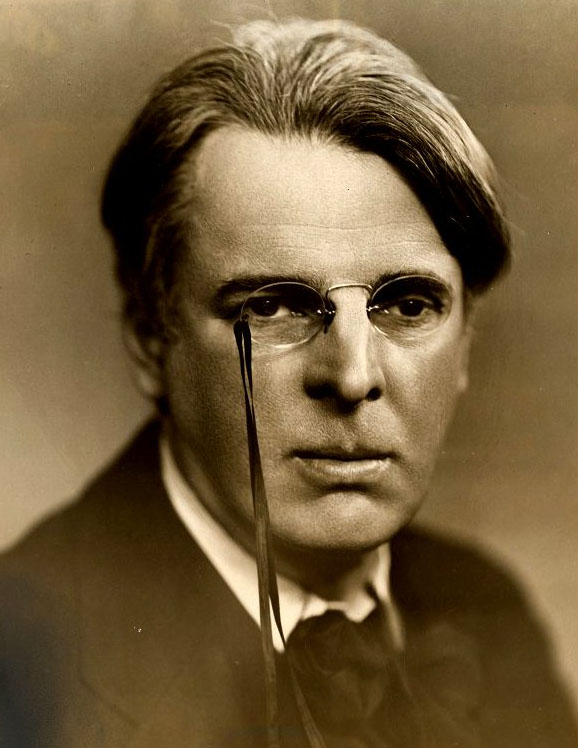

William Butler Yeats

(1865 - 1939)

What Yeats expressed, he expresses with great poetical

beauty, perfection and power and he has, besides,

a creative imagination.

SRI AUROBINDO

DECTORA:

The sword is in the rope —

The rope’s in two — it falls into the sea,

It whirls into the foam. O ancient worm,

Dragon that loved the world and help us to it,

You are broken, you are broken. The world drifts away,

And I am left alone with my beloved,

Who cannot put me from his sight for ever.

We are alone for ever, and I laugh,

Forgael, because you cannot put me from you.

The mist has covered the heavens, and you and I

Shall be alone for ever. We two — this crown —

I half remember. It has been in my dreams.

Bend lower, O king, that I may crown you with it.

O flower of the branch, O bird among the leaves,

O silver fish that my two hands have taken

Out of the running stream, O morning star,

Trembling in the blue heavens like a white fawn

Upon the misty border of the wood,

Bend lower, that I may cover you with my hair,

For we will gaze upon this world no longer.

FORGAEL [gathering Dectora’s hair about him]:

Beloved, having dragged the net about us,

And knitted mesh to mesh, we grow immortal;

And that old harp awakens of itself

To cry aloud to the grey birds, and dreams,

That have had dreams for father, live in us.

Sri Aurobindo’s remarks:

«It is certainly a very beautiful passage and has obviously a mystic significance; but I don’t know whether we can put into it such precise meaning as you suggest. Yeat’s contact […] is not so much with the sheer spiritual Truth as with the hidden intermediate regions, from the faery worlds to certain worlds of larger mind and life. What he has seen there, he is able to clothe rather than embody in strangely beautiful and suggestive forms, dreams and symbols. I have read some of his poems which touch these behind-worlds with as much actuality as an ordinary poet would achieve in dealing with physical life — this is not surprising in a Celtic poet, for the race has the key to the occult worlds or some of them at least — but this strange force of suggestive mystic life is not accompanied by a mental precision which would enable us to say, it is this ir that his figures symbolises. If we could say it, it might take away something of that glowing air in which the symbol stand out with such a strange unphysical reality. The perception, feeling, sight of Yeats in this kind of poetry are remarkable, but his mental conception often veils itself in a shimmering light — it has then shining vistas but no strong contours.»

«In Yeats, a supreme artist in rhythm, this spiritual intonation is the very secret of all his subtlest melodies and harmonies and reveals itself whether in the use of old and common metres which cease to be either old or common in his hands or in delicate new turns of verse. We get it in its blank verse, taken at random, —

A sweet miraculous terrifying sound, —

or in the mounting flight of that couplet in the flaming multitude

That rise, wing upon wing, flame above flame

And like a storm cry the ineffable name.

or heard through the slowly errant footfalls of that other,

In all poor foolish things that live a day

Eternal Beauty wandering on the way, —

but most of all in the lyrical movements, —

With the earth and the sky and the water, remade, like a casket of gold;

For my dream of your image that blossoms a rose in the deeps of my heart?

There we have, very near to the ear of the sense, that inaudible music floating the vocal music, the song unheard, or heard only behind and in the inner silence, to catch some echo of which is the privilege of music but also the highest intention of poetical rhythm.»

«The perfection here of Yeats’ poetic expression of things occult is due to this that at no point has the mere intellectual or thinking-mind interfered — it is a piece of pure vision, a direct sense, almost sensation of the occult, a light not of earth flowing through without anything to stop it or to change it into a product of the terrestrial mind. When one writes from pure occult vision there is this perfection and direct sense though it may be of different kinds, for the occult world of one is not that of another. But when there is the intervention of the intellectual mind in a poem this intervention may produce good lines of another power, but they will not coincide in tone with what is before them or after — there is an alternation of the subtler occult and the heavier intellectual notes and the purity of vision becomes blurred by the intrusion of the earth-mind into a seeing which is beyond our earth-nature.

But these observations are valid only if the object is as in Yeats’ lines to bring out a veridical and flawless transcript of the vision and atmosphere of faeryland. If the object is rather to create symbol-links between the seen and the unseen and convey the significance of the mediating figures, there is no obligation to avoid the aid of the intellectualising note. Only, a harmony and fusion has to be effected between the two elements, the light and beauty of the beyond and the less remote power and interpretative force of the intellectual thought-links. Yeats does that, too, very often, but it does it by bathing his thoughts also in the faery light; in the lines quoted, however, he does not do that, but leaves the images of the other world shimmering in their own native hue of mystery. There is not the same beauty and intense atmosphere when a poem is made up of alternating notes. The finest lines are those in which the other-light breaks out most fully — but there are others too which are very fine too in their quality and execution.»

«I do not think I have been unduly enthusiastic over Yeats, but one must recognise his great artistry in language and verse in which he is far superior to A.E. — just as A.E. as a man and a seer was far superior to Yeats. Yeats never got beyond a beautiful mid-world of the vital antariksha, he has not penetrated beyond to spiritual-mental heights as A.E. But all the same, when one speaks of poetry, it is the poetical element to which one must give the most importance.»

Two Songs from a Play

I

I saw a staring virgin stand

Where holy Dionysus died,

And tear the heart out of his side,

And lay the heart upon her hand

And bear that beating heart away;

And then did all the Muses sing

Of Magnum Annus at the spring,

As though God’s death were but a play.

Another Troy must rise and set,

Another lineage feed the crow,

Another Argo’s painted prow

Drive to a flashier bauble yet.

The Roman Empire stood appalled:

It dropped the reins of peace and war

When that fierce virgin and her Star

Out of the fabulous darkness called.

II

In pity form man’s darkening thought

He walked that room and issued thence

In Galilean turbulence;

The Babylonian starlight brought

A fabulous, formless darkness in;

Odour of blood when Christ was slain

Made all Platonic tolerance vain

And vain all Doric discipline.

Everything that man esteems

Endures a moment or a day.

Love’s pleasure drives his love away,

The painter’s brush consumes his dreams;

The herald’s cry, the soldier’s tread

Exhaust his glory and his might:

Whatever flames upon the night

Man’s own resinous heart has fed.